By Tyson Thorne

830 BC? 595 BC? No one seems to know for certain when Joel was written, or even who wrote it. Joel was a common Old Testament name, meaning “The Lord is God.” Not much is known about the author of the book, save what he tells us about himself, which is almost nothing. The book itself gives no reference to any datable historic events. Locust plagues, though infrequent, occur often enough in the Near East to be of no assistance in dating the book.

There are three schools of thought in regard to when Joel was written: An early preexilic date, a late preexilic date, and a postexilic date. The last of these theories, a postexilic date, is so ludicrous that we won’t even take the time to discuss it seriously. It should be sufficient to say that this theory is proposed by liberals (primarily) who cannot conceive of an all- knowing God capable of communicating future events to His people. They constantly date the prophets after the events they describe so as to discredit the incredulous miracle of God’s revelation. Not to mention that the few internal evidences they find for a late date are no evidences at all, as they describe events that have occurred frequently throughout Israel’s past. It is therefore safe to reject this theory out of hand and appropriate to spend the bulk of our time with the two preexilic theories.

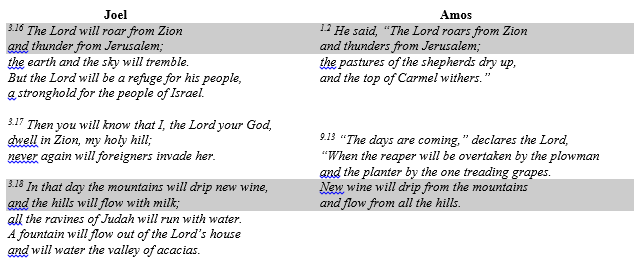

Early Preexilic Theory. The placement of the book in the canon, the references to Tyre, Sidon, Egypt, Edom and Philistia in the book, the fact that the practices described were in effect at in the ninth century BC, and that the message of Amos (known to have been written circa 760 BC) depends upon the people being familiar with Joel’s message are all arguments for an early preexilic date. There are weaknesses to many of these views, but not critical ones. For instance, though the canon is largely arranged in an historical fashion, early books first, later books last, the position of Joel in the Septuagint is different. Though this argument is not strong, it does necessitate proving that the traditional canonical placement of the book is wrong, which no scholar has yet done. The second argument is fairly strong. The mention of Israel’s enemies is not Assyria, or Babylon, but nations who were no longer Israel’s concern in 595 BC. Some have argued that chapter two is a vivid enough description of Babylon that to name them for a contemporary audience is unnecessary, but this is an argument from silence and therefore invalid. The third evidence, that all the practices described in the book existed during the ninth century, is weak. The practices described originated around 950 BC and were re- instituted largely after the exile. This argument would be true of all three theories, but is important to note insofar as pointing out that these practices would not be uncommon for the Israelites of 830 BC. The final argument, that the book of Amos depends upon Joel’s message being widely known, is perhaps the most difficult to prove. Does Amos truly depend on Joel’s being a precursor? Perhaps. It appears that Amos may have quoted from the final prophecy of Joel at both the beginning and the ending of his book. If true, there are many posible ramifications, including Dr. Benware’s assertion that “Amos took the keynote of his prophecy from the closing word’s of Joel’s prophecy.” Examine the parallel’s below.

Though not conclusive, it is interesting to note how closely these verses parallel each other, especially since Amos records them at the beginning and ending of his book.

Late Preexilic Theory. Essentially, a late preexilic date merely moves the book closer to the time of the events it describes happening in “The Day of the Lord.” By moving the date of writing to between 597 and 587 BC the book would fit nicely with other late prophets who refer to the Day of the Lord as the destruction of the temple and Jerusalem in 586 BC. The harmonization of this “Day of the Lord” with the other prophets is what makes this view so attractive. Because so little historic information exists regarding the date of composition, this view is perhaps as likely as the Early Preexilic Theory. If this dating is correct, Joel would then be no one’s contemporary, a lone prophet of God.

Final Analysis. Because of the mention of early enemies of Israel, no mention of Assyria or Babylon, and the possibility of Amos’ quoting of Joel, this author leans toward an early preexilic date of composition, while recognizing the complete validity of the Late Preexilic theory.

Big Idea

Only Israel’s national repentance can turn “the Day of the Lord” into a time of blessing.

The Book

Historical Visitation, chapter 1. Joel’s message was based on two recent natural disasters: a great plague of locusts (verses two through four) and a great drought (verses 15-20). Joel interpreted these actions against the land as judgments of God, and shouted his message to awaken God’s people who slumbered in moral depravity. Joel launches from these two crisis events in chapter one, to a look at two times of great desolation in the future.

Prophetic Revelation,chapters 2-3. The “Day of the Lord” (which, in the great span of history refers to the Tribulation, but in Israel’s history also referred to the Assyrian and Babylonian invasions), was immanent, but the people still had time to repent.

|

|